According to the Social Security Administration (SSA), there have been over 91,000 different names given to babies since 1880 in the US. We can think of the process of naming children as a market activity. The “market” consists of parents (i.e. consumers) who select a name (i.e. product) from a wide assortment of options. For the purposes of this present analysis, we ignore a market’s “sellers” as they aren’t relevant. Nevertheless, we can perform a traditional market analysis of names to see whether the market became more or less concentrated over time. A highly concentrated market means that only a few names (e.g. John, David, Mary, or Elizabeth) are assigned over and over again and therefore represent the majority of birth names in a given year.

Within economics, a standard method of measuring market concentration is using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The Index converts market shares of all of the market’s participants into a single number ranging from 0 to 1 (or alternatively stated as 0 to 10,000) with 0 representing a perfectly competitive market and 1 representing a complete monopoly. The Department of Justice uses this same metric when evaluating anti-trust concerns associated with potential mergers and acquisitions.

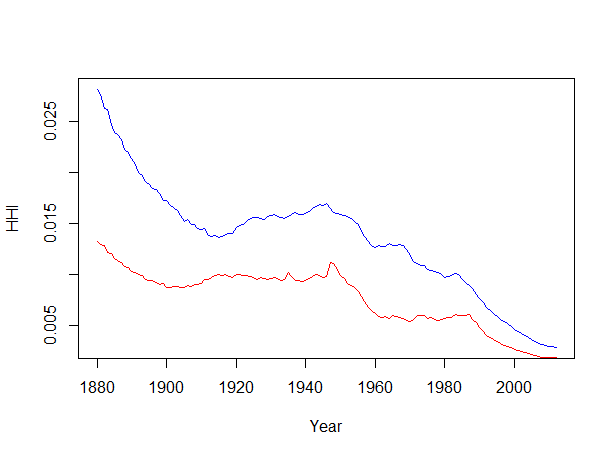

Using the yearly name data provided by the SSA, we calculated the HHI by gender for every year since 1880. In general, the name market is highly fragmented, which comes as no surprise since we began with this discussion by acknowledging that 91,000 names have been given during this time period. The chart below shows the HHI for the boys’ and girls’ name markets for every year since 1880 in blue and red respectively.

Over the entire period, the boys’ name market has been more concentrated relative to its female counterpart. However, both name markets have become significantly less concentrated with time. Part of this decrease is artificially created by virtue of how the data was collected. Each name is only counted if a person registers for a Social Security card and submits gender information. According to the SSA, we know that registration completeness improved dramatically from 1880 to 1937. By the early 1940s, most new births in the US were recorded with the SSA dataset. This means that for the period preceding 1937, name diversity and market share are likely omitted, thereby biasing the estimates of market concentration upward. Nevertheless, we see an unmistakable downward trend during the period for which we have accurate data.

We can think of several hypotheses to explain this fragmentation. First, new immigrant groups probably introduce new names to the market. What matters for this mechanism is not that large volumes of immigrants come to the United States, but that many different, previously unrepresented immigrant groups arrived in the US and now participate in the name market. Second, it’s possible that parents increasingly desire to be unique and cool by avoiding “mainstream” names. Third, it’s possible that the name market naturally grows in diversity over time because names never really “die.” Antiquated names often lose popularity, but they stick around because children continue to be named in honor of older relatives.